Marshall McLuhan said “the medium is the message” – meaning every new medium changes the way we interact with the world, including the message within that medium. While obvious in the present day, where the internet has dramatically shaped our daily lives, we need not stray far from McLuhan’s own time for another poignant example: underground newspapers. While not strictly a “new” medium, the US underground press boom of the Sixties rose out of a newly available process – offset printing made it possible to start a publication with a smaller investment of time and money than with the previously dominant process of letterpress, resulting in a massive boom in independent publications.

From there, we can see similarities between the underground boom of the Sixties and the online boom of the past few decades. Both were made possible by newly available technology, opened up dialogues which were not possible under the oversight of the previous mass media monopoly gatekeepers, and radically changed society.

To make more of these underground papers accessible, I have digitized a few papers which I could not easily find online. You can find them on my Internet Archive account. Note that the presence of a digitized publication on my account does not amount to an endorsement. The underground press scene was run predominantly by cis heterosexual white men. As such, there is much transphobia, homophobia, racism, misogyny, and other chauvinistic expressions within the papers.

Embracing Subjectivity

A feature of most radical press movements is the throwing out of journalistic “objectivity” – the idea that a journalist should state facts plainly without pushing any particular agenda. While this idea of objectivity is the bread and butter of most mainstream news media, the radical press has no use for this concept – the agenda of radical publishers is rarely concealed, because the purpose of publishing is agitation into action.

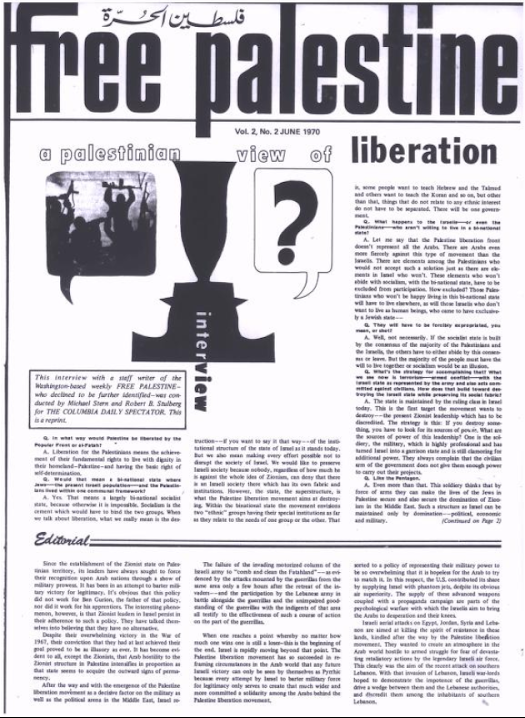

For example, Free Palestine, a paper closely tied to the Palestinian resistance of the time, edited by Arab-American lawyer and activist Abdeen Jabara, is a paper with a clear agenda, with a call to action on the front of every issue. They engaged in dialogue with others who did not entirely agree with their perspective, but there is no question of what the editors were really trying to say.

(It is worth noting that Jabara and his clients were targets of the National Security Agency (NSA) in the late 60s. Decades old at that point, the NSA was still not known to the general public, operating mostly in secret.)

In the present, this issue continues to challenge the so-called “objectivity” of mainstream media. Often it is framed as being “too complicated” for the subjectively-minded masses to fully understand. This appeal to “objectivity” ironically conceals what the occupation objectively is: a textbook case of settler colonial occupation and genocide, to which according to international law the Palestinian people have a legal right to resist. A powerful resistance to this facade of “objectivity” has swept social media platforms on an unprecedented scale for going on half a year, thanks in part to mobilization by Palestinian and anti-Zionist activists over social media.

Editing as Moderation

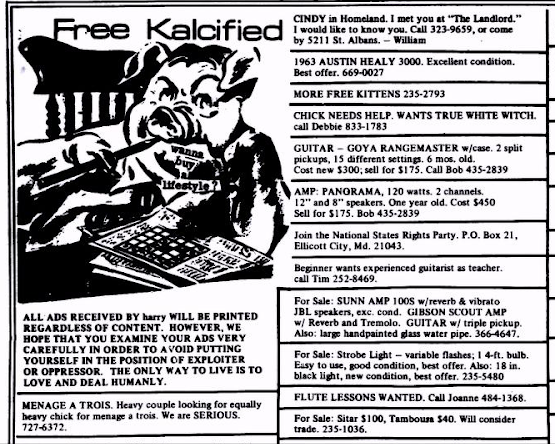

A typical underground paper featured little editing and accepted most submissions. This was intentional – the underground press championed free speech when mass media was dominated by even fewer corporations. However, it evokes the social media “moderation problem” – if you let anyone on your platform, that means anyone, including Nazis. Such an issue arises in Harry, the Baltimore Underground Journal.

Seven issues in, the team at Harry opened up the classified ads to everyone. Many ads were just chauvinist men soliciting sex. In one issue, there was a recruiting ad for the National States Rights Party. The paper assumed more editorial control over the classifieds after the sex solicitation became too much, bizarrely deeming the NSRP ad as “non-exploitative and not racist[…] though the organization is.” Soon after, they published a letter criticizing the paper for publishing both the ad and an article which dismissed socialism as being for “pigs” and “hard hats” in reaction to criticisms of Harry by a group which editor Thomas D’Antoni described as “theory-crazed Stalinist political personages”.

This kind of conflict should feel familiar if you’ve spent significant time in online communities. When a space isn’t well moderated, chauvinist bad actors can come in and make the space hostile. When there’s a stated tolerance of chauvinism, the problem becomes worse. It therefore must be a priority to draw clear boundaries of acceptability. Many underground publishers only reluctantly adopted this priority.

Okay, But Where Are The Memes?

Defined very broadly, a meme is like an in-joke for a mass audience. The sources of memes are often copyrighted, but not as a rule – it’s more about what little chunks of culture resonate with people than the legality of using that chunk for your own purposes. Relaxed attitudes towards copyright allow for memes to spread. That attitude was as endemic in underground press as it is in online communities.

A notorious example was R. Crumb’s “Keep on Truckin’!”, a comic which spread across the underground without his explicit permission. The meme became so popular that companies like A.A. Sales made unofficial merchandise. When Crumb tried to sue A.A. Sales, the comic was ruled to be in the public domain due to a since-rescinded technicality. (Crumb’s appeal to the Sixties underground aside, he often used racial caricature and sexual violence in his work, something he intensified to shake off his popularity. As such, recent critical assessments don’t favor him.)

There are Similar stories of meme ascension for digital-era cartoonists such as Matt Furie, whose Pepe the Frog became a right-wing signifier. K.C. Green’s work has also hit meme status several times, most famously his “This is Fine” comic. Each of these artists has responded to their work being used in this way with new works which subvert (or rebuke) the audience’s expectations.

A few other memes of the Sixties underground include satirical portrayals of Nixon, the cryptic “Paul is dead” rumors regarding Paul McCartney, and the chorus of Arlo Guthrie’s Alice’s Restaurant, a song which encouraged its own memetic spread.

Newsprint, Digital Storage, and Ephemerality

There is one reason why I was able to explore the underground press of the Sixties several decades later at the Pratt: microfilm. Newsprint is fragile, not meant to last long beyond its initial publication. Archival-quality microfilm can last anywhere between 100-500 years, if properly stored and handled. If it weren’t for the efforts of one very dedicated Bell and Howell employee in 1973, much of what exists on those rolls would be entirely lost to time.

The ephemerality of newsprint is matched by that of digital storage. While a data server for a social media app may carry its contents more reliably than a newsprint for a time, it’s still easy for that data to become lost forever. A devastating example of this is Myspace. In 2019, the former social media juggernaut lost 12 years of data overnight. It’s hard to overstate how much was lost in just this one incident, including 50 million songs from 12 million musical artists.

The issue of archiving the web and digital media is complicated. Due to the truly staggering quantity of data, you cannot possibly archive everything online. The Internet Archive can only do selective crawls of the web, which capture a website on a particular day and store it on their servers. This is the best way to get as much of the web archived as possible, but because of the possibility of significant data loss inherent in digital storage, it is not the best long-term archival solution. The tradeoff of storing as much as possible means accepting a certain level of ephemerality.

While this is a problem with no perfect answers, I do believe that microfilm should be considered as one of many imperfect answers. One could curate a collection of digital media, say social media posts of a particular time or subject, and store that collection on microfilm, so that a permanent archive can exist outside of its ephemeral origin. As of the time of publishing this article, I am unaware of any such project. If you or anyone you know is doing something similar, or is interested in starting such a project, I would absolutely love to know about it. You can reach me via my email: jbreck@prattlibrary.org.

This post was originally published in part on the Pratt Chat blog.

Further Reading Recommendations

- Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press And The Rise of Alternative Media in America by John McMillian

- Voices from the Underground: Insider Histories of the Vietnam Era Underground Press, edited by Ken Wacshberger

- People’s Movements, People’s Press: The Journalism of Social Justice Movements by Bob Ostertag

- Protest on the Page: Essays on Print and the Culture of Dissent Since 1865, edited by James L. Baughman, Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen & James P. Danky

- Protest History: Underground Press Syndicate, a series of posts by librarian Laurie Charnigo on the Underground Newspapers Collection

- A Short Guide to Baltimore Underground Newspapers (1968-1970), a post by John Duda on local contributions to the Underground Newspapers Collection, originally hosted on the now-defunct Indypendent Reader website.

Leave a comment